Introduction

Background

Oral pigmentation is a relatively common condition that may involve any portion of the oral cavity. Multiple causes are known, and they may range from simple iatrogenic mechanisms, such as implantation of dental amalgam, to complex medical disorders, such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Local irritants, such as smoking, may also result in melanosis of varying degrees. Oral pigmented lesions result from cellular hyperplasia that can range from benign nevi to fatal oral melanoma.

Pigmented entities may arise from intrinsic and extrinsic sources. The color may range from light brown to blue-black. The color depends on the source of the pigment and the depth of the pigment from which the color is derived. Melanin is brown, yet it imparts a blue, green, or brown color to the eye. This effect is due to the physical properties of light absorption and reflection described by the Tyndall light phenomenon or effect.

Oral conditions associated with increased melanin are common; however, those due to melanocytic hyperplasias are rare. Clinicians must visually inspect the oral cavity, obtain clinical histories, and be willing to perform a biopsy for any condition that is not readily diagnosed. Patients with oral malignant melanoma often recall having an existing oral pigmentation months to years before diagnosis, and the condition may even have elicited prior comment from physicians or dentists.

Pathophysiology

Four different types of oral pigmentation are described in detail to illustrate the 4 major mechanisms leading to increased oral pigmentation: oral pigmentation due to intrinsic processes (eg, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome), oral pigmentation due to extrinsic processes (eg, amalgam tattoo), oral pigmentation due to hyperplastic or neoplastic processes (eg, melanoma), and iatrogenic oral pigmentation (eg, smoker melanosis).

Oral pigmentation due to intrinsic processes

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by intestinal hamartomatous polyps in association with mucocutaneous melanocytic macules. Pigmented macules, often confluent and varying in size and shades of brown, appear in almost all cases periorally and on the lips and buccal mucosae. Any oral site may be involved, and the degree of pigmentation and oral involvement vary among affected individuals. Pigmented macules on the cutaneous surfaces covering the extremities and face are less frequently observed. The relative risk of developing cancer in this syndrome is increased 15-fold compared with that of the general population. The cancer primarily involves the GI tract (including the pancreas and the luminal organs), the female and male reproductive tracts, and the lungs.

Oral pigmentation due to extrinsic processes

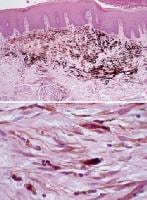

The amalgam tattoo appears as a soft, painless, nonulcerated, blue/gray/black macule with no surrounding erythematous reaction. It is most frequently found on the gingival or alveolar mucosa, but many cases are also seen on the buccal mucosa. The tattoo is found more frequently in females than in males, probably because females are more likely to seek dental care. It is also seen more frequently with advancing patient age, presumably because of increased exposure to dental procedures over time. The tattoo is only moderately demarcated from the surrounding mucosa and is usually less than 0.5 cm in greatest diameter. Lesions with larger particles might be visible on dental radiographs.

Some patients demonstrate a long-term inflammatory response, with small, discolored papules produced, and in those who exhibit a strong macrophage response, the discolored patch can enlarge over time as the macrophages engulf the foreign material and attempt to move it out of the area.

Occasionally, deposits of amalgam are found in bone, usually as a result of the material being inadvertently dislodged from an adjacent restoration during tooth extraction or other surgical procedure, including the deliberate placement of amalgam into the apical canal of a root during endodontic surgery. These quickly become blackened and may impart a black discoloration to the adjacent bone.

Oral pigmentation due to hyperplastic or neoplastic processes

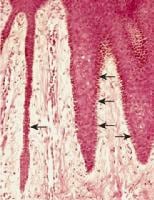

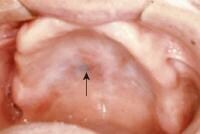

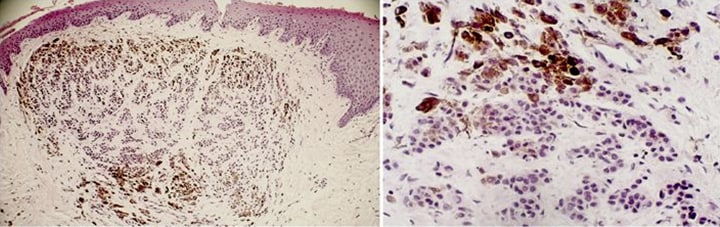

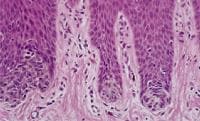

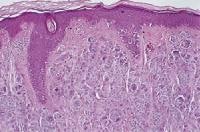

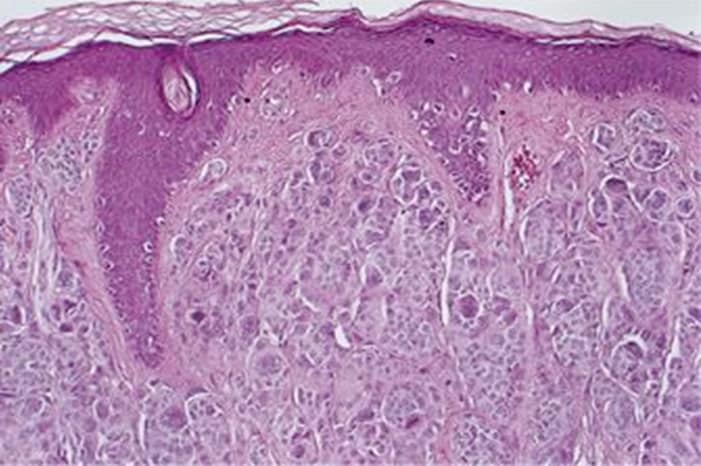

Melanotic macules may be solitary or multiple and can involve the gingiva, lip, as shown below, palate, buccal mucosa, and alveolar ridge, as shown below. Microscopically, this melanin deposit is mainly in the basal cell layers. Melanin may also be seen in the connective tissue near the basal cell layer, as shown below.

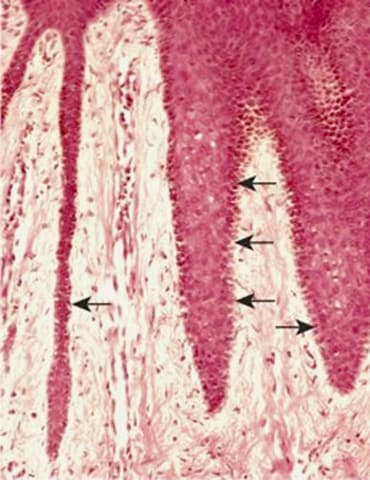

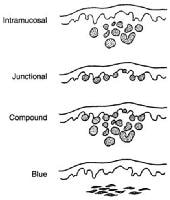

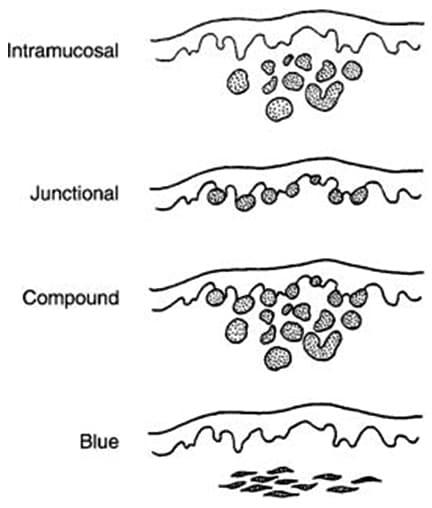

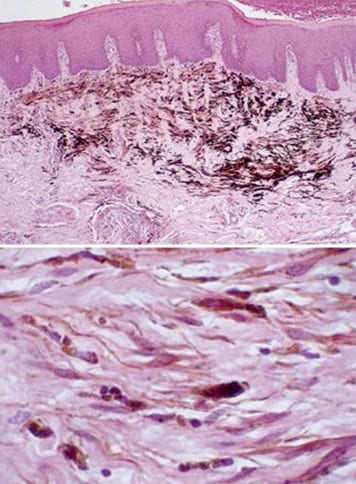

Oral nevi are uncommon in the oral cavity. When they are present, they appear most commonly on the palate or gingiva. They can be intramucosal, junctional, compound, or blue nevi, shown below.

Clinically, they appear as brown and black elevated papules, as shown below.

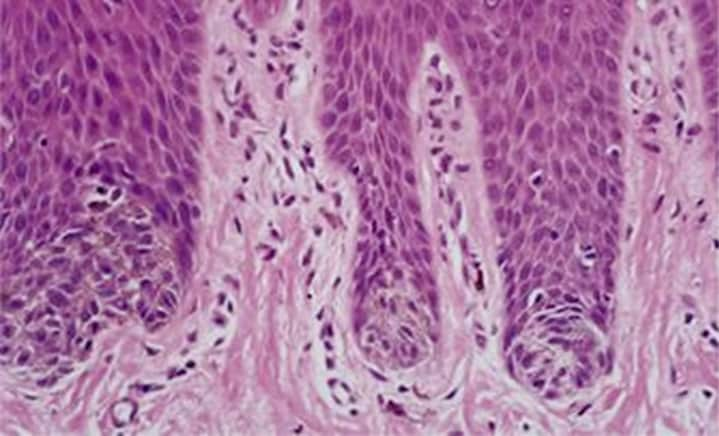

Microscopically, the nest of nevi cells is laden with melanin and is seen below the basal cell layer (intramucosal nevus, as shown below), at the junction of basal layers (junctional nevus, as shown below, in both sites (compound nevus, as shown below), or deep in the connective tissue (blue nevus, as shown below). Excision of these lesions is required to rule out other serious pigmented lesions.

Junctional nevi are uncommon and are thought to arise primarily from melanocytes in the basal layer of the squamous mucosa. Junctional nevi reportedly can undergo malignant transformation to melanoma.

Oral melanomas are uncommon, and, similar to their cutaneous counterparts, they are thought to arise primarily from melanocytes in the basal layer of the squamous mucosa. The melanocytic density has a regional variation. In the oral mucosa, melanocytes are observed in a ratio of approximately 1 melanocyte to 10 basal cells. In contrast to cutaneous melanomas, which are etiologically linked to sun exposure, risk factors for oral melanomas are unknown. These melanomas have no apparent relationship to chemical, thermal, or physical events (eg, smoking; alcohol intake; poor oral hygiene; irritation from teeth, dentures, or other oral appliances) to which the oral mucosa is constantly exposed. Although benign, intraoral melanocytic proliferations (junctional nevi) occur and are potential sources of some oral melanomas; the sequence of events is poorly understood in the oral cavity.

Currently, most oral melanomas are thought to arise de novo. Although rare, tumor transformation of nevi to melanoma involves the clonal expansion of cells that acquire a selective growth advantage. This transformation of melanocytes in an existing nevus, or of single melanocytes in the basal cell layer, must occur before the altered cells proliferate in any dimension. The oral mucosa has an underlying lamina propria, not a papillary and reticular dermis with easily discernible boundaries as is observed in skin. This architectural difference obviates the use of Clark levels for describing mucosal melanomas.

Iatrogenic oral pigmentation

Most iatrogenic pigmented lesions in the oral cavity are benign and their pigmentation is due to excessive production of melanin, which is produced by melanocytes. These cells are specialized dendritic cells present in the basal cell layer of the mucous membrane. The clinical visible pigmentation in the oral cavity depends on the number of melanocytes or the degree of melanin produced by these cells. The range of color pigmentation varies from gray to brown to black to dark blue. The closer the pigmentation to the surface, the darker the color (black); a melanin deposit before the basal cell layer will cause blue color.

Smoker’s melanosis is due to long-term tobacco smoking. The pigmentation is usually distributed along the gingival layer in the upper and lower anterior teeth. It may also be seen in the soft palate, buccal mucosa, and floor of the mouth. Smoking cessation is the treatment of choice. The hyperpigmentation then disappears in a few months.

Actinic lentigo is also referred to as a solar lentigo. Lentigo presents as light-tan macules on the face, but it also may involve the upper (and especially) the lower lip as a result of sun exposure. It is common in elderly white persons. Microscopically, marked melanin pigments are present within the basal keratinocytes.

Melasma is a symmetric hyperpigmentation of the face and, at times, the lips. It is usually associated with pregnancy or oral contraceptive intake, along with exposure to sunlight. Microscopically, increased melanin is present in the keratinocytes and superficial connective tissue.

Frequency

United States

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is rare, with a frequency of approximately 1 case per 60,000-300,000 people.

Although surveillance data on amalgam tattoo are not available, this is considered a very common lesion.

Oral nevi are not very common. Surveillance data are not available for oral melanoma alone. Data for oral melanoma are included in the combined statistics for oral cancer. In a review of the large studies, melanoma of the oral cavity reportedly accounts for 0.2-8% of melanomas and approximately 1.6% of all malignancies of the head and neck. In some studies, primary lesions of the lips and nasal cavity are also included in the statistics, thereby increasing the incidence. The oral mucosa is primarily involved in less than 1% of melanomas, and the most common locations are the palate and the maxillary gingiva. Metastatic melanoma most frequently affects the mandible, the tongue, and the buccal mucosa. In contrast to the incidence of cutaneous melanoma, the incidence of oral melanoma has remained stable for more than 25 years.

Iatrogenic oral pigmentation is not very common, with the exception of smoker’s melanosis, which is seen in persons who smoke heavily.

International

The international frequency of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is unknown.

Although surveillance data on amalgam tattoo are not available, this is considered a very common lesion.

Internationally, data on oral nevi are not available; however, oral melanoma makes up a higher percentage of the total number of melanomas in Japanese persons compared with other groups. In Japan, oral melanomas account for 11-12.4% of all melanomas, and males may be affected slightly more commonly than females. This percentage is higher than the 0.2-8% reported in the United States and Europe. Because cutaneous melanoma is less common in persons of more darkly pigmented races, people of these races have a greater relative occurrence of oral mucosal melanoma.

Internationally, no data are available for iatrogenic oral pigmentation.

Mortality/Morbidity

- The principal causes of morbidity in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome stem from the intestinal location of the polyps (eg, small intestine, colon, stomach).

- Morbidity includes small intestinal obstruction and intussusception (43%), abdominal pain (23%), hematochezia (14%), and prolapse of a colonic polyp (7%); these conditions typically occur in the second and third decades of life.

- Almost 50% of patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome develop and die from cancer by age 57 years.1,2 The mean age at first diagnosis of cancer is 42.9 ± 10.2 years. The cumulative risk of developing any cancers associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in patients aged 15-64 years is 93%.

- The cumulative risks of developing a particular cancer from ages 15-64 years are as follows: esophagus, 0.5%; stomach, 29%; small intestine, 13%; colon, 39%; pancreas, 36%; lung, 15%; testes, 9%; breast, 54%; uterus, 9%; ovary, 21%; and cervix, 10%.

- No morbidity is associated with the amalgam tattoo. This lesion is only of cosmetic significance.

- No mortality is associated with oral nevi, with the exception of junctional nevi, which can give rise to melanoma. Oral melanoma, however, is often overlooked or clinically misinterpreted as a benign pigmented process until it is well advanced. Radial and vertical extension is common at the time of diagnosis.

- The anatomic complexity and lymphatic drainage of the region dictate the need for aggressive surgical procedures.

- The prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival rate generally in the range of 10-25%. The median survival rate is less than 2 years.

- As a result of the absence of corresponding histologic landmarks in the oral mucosa (ie, papillary and reticular dermis), Clark levels of cutaneous melanoma are not applicable to those of the oral cavity. Conversely, tumor thickness or volume may be a reliable prognostic indicator. The relative rarity of mucosal melanomas has dictated that tumor staging be based on the broader experience with cutaneous melanoma.

- Oral melanomas seem uniformly more aggressive, and they spread and metastasize more rapidly than other oral cancers or cutaneous melanomas.

- No known mortality is reported with iatrogenic pigmented oral lesions.

Race

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome has been described in persons of all races.

- No data suggest an increased prevalence of amalgam tattoo in persons of any particular race.

- Oral nevi are seen in persons of all races. Oral melanoma is reportedly more common in Japanese persons than in other groups. This observation is based on a review of frequently cited historical literature.

- Iatrogenic pigmented lesions are seen in persons of all races.

Sex

- In Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, the male-to-female ratio is approximately equal.

- Amalgam tattoo seems to have a predilection for females, most likely because females are more likely to seek routine dental care.

- A female predilection is reported for oral nevi and a male predilection exists in oral melanoma, with a male-to-female ratio of almost 2:1. Oral melanoma is diagnosed approximately a decade earlier in males than in females. This ratio is contrasted with the roughly equal sex distribution of cutaneous melanoma. In Japan, data suggest an equal or slight male predilection.

- A female predilection is reported for iatrogenic oral pigmentations.

Age

- The average age at diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is 23 years in men and 26 years in women.

- Amalgam tattoo lesions are most often observed in persons in their third to sixth decades of life, but they are present in persons from all age ranges.

- Oral nevi are usually seen in younger persons, while malignant melanoma is largely a disease of persons older than 40 years, and it is rare in patients younger than 20 years. The average patient age at diagnosis is 56 years. Oral malignant melanoma is commonly diagnosed in men aged 51-60 years, whereas it is commonly diagnosed in females aged 61-70 years.

- Oral iatrogenic pigmentations are seen in all age groups.

Clinical

History

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

- A family history of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome may be present.

- Repeated bouts of abdominal pain in patients younger than 25 years may be noted.

- Unexplained intestinal bleeding in a young patient may be present.

- Tissue from the rectum may be prolapsed.

- In females, menstrual irregularities (due to hyperestrogenism from sex cord tumors with annular tubules) may be present.

- Precocious puberty may be noted.

- Amalgam tattoo: A history of dental restorations must be present.

- Nevi and melanoma: Oral nevi could arise spontaneously anywhere in the oral cavity and lips. Oral melanomas arise silently, with few symptoms noted until progression has occurred. Most people do not inspect their oral cavity closely, and melanomas are allowed to progress until significant swelling, tooth mobility, or bleeding causes them to seek care. Pigmented lesions ranging from 1 mm to 1 cm or larger are found. Reports of previously existing pigmented lesions are common. These lesions may represent unrecognized melanomas in the radial growth phase.

- Iatrogenic pigmented lesions are found most commonly in persons who smoke heavily and in females taking contraceptive pills.

Physical

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

- Cutaneous pigmentation (1- to 5-mm macules) of the perioral region crosses the vermilion border (94%) and the perinasal and perioral areas.

- Lesions may be present on the fingers and the toes, on the dorsal and volar aspects of the hands and the feet, and around the anus and the genitalia.

- The pigmentation may fade after puberty.

- Mucous membrane pigmentation is primarily on the buccal mucosa (66%) and rarely on the intestinal mucosa.

- A rectal mass (rectal polyp) may be observed.

- Gynecomastia and growth acceleration (due to Sertoli cell tumor) may be found.

- In males, a testicular mass may be present.

- Amalgam tattoo: Dark macular lesions, which are often bluish, are seen.

- Nevi and melanoma

- Oral nevi are often seen by dentists during routine oral examinations. Malignant melanomas are often clinically silent, and they can be confused with a number of asymptomatic benign pigmented lesions. Oral melanomas are largely macular, but nodular and even pedunculated lesions can occur.

- Pain, ulceration, and bleeding are rare in persons with oral melanoma until late in the disease course.

- The pigmentation varies from dark brown to blue-black; however, mucosa-colored and white lesions are occasionally noted, and erythema is observed when the lesions are inflamed.

- The palate and the maxillary gingiva are involved in approximately 80% of patients, but lesions are also identified on the buccal mucosa, the mandibular gingiva, and the tongue. The oral mucosa is primarily involved in less than 1% of melanomas. Metastatic melanoma most frequently affects the mandible, the tongue, and the buccal mucosa.

- Features of long-standing lesions include elevation, color variegation, ulceration, and satellite lesions that may have the appearance of physiologic pigmentation.

- A neck mass may be present, indicating regional metastasis; however, this is rare unless the primary tumor is extensive.

- Amelanotic melanoma accounts for 5-35% of oral melanomas. This melanoma appears in the oral cavity as a white, mucosa-colored, or red mass. The lack of pigmentation contributes to clinical and histologic misdiagnosis.

- Iatrogenic pigmented lesions: These appear as pigmented macules or papules that are smaller than 6 mm in greatest diameter.

Causes

- The cause of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a germline mutation of the STK11 gene, located on band 19p13.3. The related protein is likely regulated by phosphorylation by cyclic adenosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase A.3

- Amalgam tattoo is caused by the implantation of amalgam particles in the oral mucosa by the spray of high-speed handpieces or by direct unintentional implantation during dental extractions. Restorations at the gingival margin can also cause this lesion.

- The cause of oral nevi or melanoma of any mucosal surface remains unknown, and the incidence has remained stable for more than 25 years. In contrast, cutaneous lesions are directly linked to fair-skinned and blue-eyed persons with a history of blistering sunburns, and the incidence has increased dramatically over the same period.

- The causes of iatrogenic pigmented lesion are smoking, sun exposure, and contraceptive pills. The Medscape Smoking Resource Center may be helpful.

I was diagnose with genital warts since 2012 i have be taking lot treatment and all i got is outbreak. in 2015 I gave up the treatment because I can't continues wasting time and money on treatment at the end it will not cure me. about 6 weeks ago i did natural research online I had So many people talking good about natural remedy, after the research i was recommended to Dr onokun, And I wrote to him through his email and told him my problem after some conversations with him he gave me natural treatment after 1 week Dr onokun treated me i got cured permanently. and i went to see my doc he confirmed that the diseases has gone out from my body. every patients should know there is 100% natural hpv cure. contact Dr onokun his email address: dronokunherbalcure@gmail.com

Trả lờiXóaNhận xét này đã bị tác giả xóa.

Trả lờiXóaNhận xét này đã bị tác giả xóa.

Trả lờiXóa