Mumps

Background

Mumps, also known as epidemic parotitis, is an acute generalized infection observed in children aged 5-15 years. The viral agent belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family. The parotid glands are usually affected, whereas the submandibular and sublingual glands are generally spared. Meningitis and epididymo-orchitis are the 2 most important but less common features of this disease.

Pathophysiology

The mumps virus is a member of the Paramyxoviridae family and of the Rubulavirus genus. This genus includes the mumps virus; Newcastle disease virus; and human parainfluenza virus types 2, 4a, and 4b. Transmission of the mumps virus occurs via direct contact, via droplets, or via fomites, and it enters through the nose or mouth. More intimate contact is necessary for the spread of mumps than for measles or varicella. During the incubation period (approximately 16-18 d), the virus proliferates in the upper respiratory tract and regional lymph nodes. Viremia follows with secondary spread to the glandular and neural tissues. Inflammation of infected tissues leads to the manifestations of parotitis and aseptic meningitis. Patients are most contagious 1-2 days before the onset of parotitis.

Frequency

In the United States, prior to the use of the live-attenuated mumps vaccine in 1967, epidemics occurred every 2-5 years. The outbreaks were more frequent between January and May. Since the introduction of the mumps vaccine, a decline of more than 99% has occurred in the annual incidence of mumps in the United States. In 1986 and 1987, a resurgence of mumps occurred, with 12,848 cases reported in 1987. Most cases affected children aged 10-19 years who were born prior to the institution of recommendations for routine mumps vaccination. More recently, in 1996, approximately 750 cases were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In the United States, the most recent mumps outbreak occurred in 2006 and involved 45 states and the District of Columbia. From January 1 to October 7, 2006, 5783 cases of mumps were reported, of which 3113 (54%) were confirmed, 2612 (45%) were probable, and 58 (1%) were of unknown classification.38,39 This was the largest outbreak of mumps since 1991, when 4264 cases were reported. With regard to the 2006 outbreak, the median age was 22 years and 3644 cases (63%) occurred in females. Most of the cases were reported in individuals who had received 2 doses of measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine. It is known that 2 doses of MMR are not totally effective in preventing disease. One other contributing factor is the college campus environment, with close contact of students and the spread of mumps through respiratory and oral secretions. Another factor is that only 25 states have a college admission requirement of 2 doses of MMR vaccine.

Internationally, mumps is endemic throughout the world.

Mortality/morbidity

Deaths related to mumps are rare; more than half the deaths occur in individuals older than 19 years. Fetal deaths are increased when mumps infection occurs during the first trimester. Approximately one third of the people infected with the mumps virus are asymptomatic. Although as many as 50% of patients with mumps demonstrate inflammation of the CNS, less than 10% present with manifestations of CNS infection. Adults are at higher risk of aseptic meningitis. A common complication of mumps infection is orchitis, but sterility is rare. Other less common complications include pancreatitis and deafness.

Race

No racial predilection is reported.

Sex

Males and females are affected equally.

Age

Mumps is uncommon in infants younger than 1 year because of passive immunity acquired via placental transfer of maternal antibodies. Before the vaccine was instituted in 1967 and during the initial period of vaccination, most cases occurred in children aged 5-9 years, with 90% of cases in children younger than 15 years. In the late 1980s, a shift toward older individuals aged 5-19 years occurred. More recently, the number of cases in infants and elderly persons has increased.

Clinical history

Prodromal symptoms include a low-grade fever, malaise, lack of appetite, and headache. A day after the initial symptoms appear, reports of earache and tenderness of the parotid glands are common. One parotid gland often enlarges a few days after the other, and unilateral involvement is observed in one fourth of patients with salivary gland involvement. Once maximum parotid gland swelling has occurred, the pain, fever, and tenderness quickly diminish. The affected parotid gland returns to its normal size within 1 week. Complications of parotitis are uncommon. Recurrent acute and chronic sialadenitis are potential complications of parotitis.

Physical findings

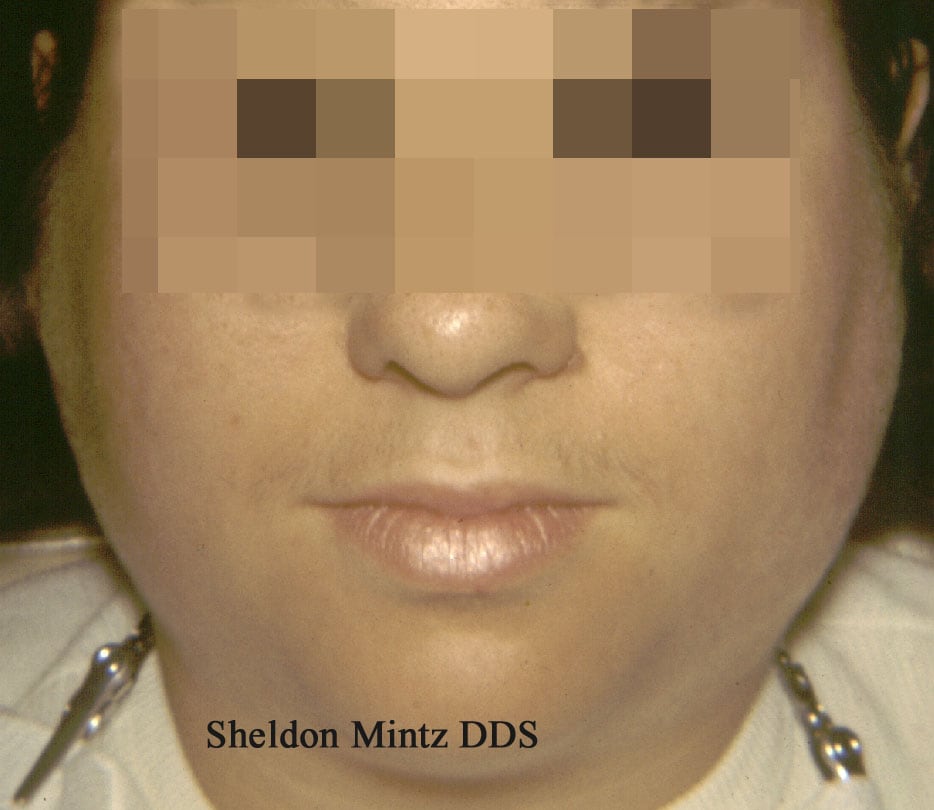

Parotitis results in enlargement and tenderness of involved parotid glands, and it is observed in 30-40% of individuals who are infected. At its most severe stage, the earlobe on the affected side lifts upward and outward. Enlarged parotid glands can also be observed when viewing the patient from behind. The enlarged parotid gland may obscure the angle of the mandible, in contrast to cervical lymphadenopathy, which does not hide this structure.

This patient with mumps has marked bilateral swelling of the salivary glands. Courtesy of Sheldon Mintz, DDS.

Intraorally, enlargement and redness of the opening of the Stensen duct of the affected gland occur. Trismus can lead to difficulty in eating and in speaking. Involvement of the submandibular glands may accompany parotitis but rarely occurs as the sole manifestation of mumps. Submandibular gland involvement is similar in presentation to that of anterior cervical lymphadenopathy. Sublingual gland involvement is least likely to occur in comparison with the other major salivary glands. Submandibular and sublingual gland involvement is usually bilateral and accompanied by swelling of the tongue.

Causes

Epidemics related to the mumps paramyxovirus have occurred in military populations and other communities, including prisons, boarding schools, ships, and remote islands. The spread of mumps in a community is also postulated to occur via children in schools and via those who secondarily infect their family members. In spite of vaccination, past outbreaks of mumps may be related to vaccine failure by using a single dose of the vaccine.

Differentials

Bilateral parotid enlargement

Infections - Parainfluenza 3 virus, coxsackievirus, influenza A virus, CMV, Staphylococcus aureus (suppurative parotitis), or HIV-related parotitis

Drug-related - Phenylbutazone, thiouracil, iodides, or phenothiazines

Metabolic

Diet

A soft diet is indicated for patients experiencing trismus.

Avoidance of citric fruit juices is recommended for patients with mumps because discomfort usually ensues when these substances are consumed.

Medication

Analgesic antipyretics may be recommended to reduce pain and discomfort from parotitis. Warm or cold packs applied to the face also may be helpful. Cases of meningitis or pancreatitis require appropriate medical attention. See Medication.

Vaccination

The mumps vaccine (Jeryl-Lynn strain) is a live-attenuated vaccine that was licensed in 1967. The mumps vaccine may be administered alone or in combination with the rubella and measles vaccines (MMR vaccine). Greater than 97% of individuals who are vaccinated develop measurable antibodies to the mumps virus. Immunity from vaccination is estimated to last more than 25 years and is believed to be lifelong in many vaccinated individuals.

Two doses of mumps vaccine are routinely recommended in all children. Doses should be administered at least 1 month apart. The first dose is usually administered on or after the child's first birthday. A second dose is administered to ensure immunity in those who do not respond to the first dose. The second dose may be administered in children aged 4-6 years. Individuals born after 1957 should show documentation of at least 1 dose of the MMR vaccine. If this documentation is not available, a single dose of the MMR vaccine should be administered.

Follow-up

Complications

In the CNS, aseptic meningitis is a relatively common complication that does not cause symptoms in 50-60% of patients. Aseptic meningitis manifests with symptoms of headache and stiff neck in approximately 15% of patients. Resolution occurs in 3-10 days.

Orchitis (testicular inflammation) is one of the most common complications of mumps infection. It occurs in approximately 20-50% of postpubertal males, usually after the onset of parotitis. Symptoms include testicular swelling and tenderness, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Pain and swelling diminish after 1 week, but tenderness may continue for several weeks. Testicular atrophy occurs in 50% of patients with orchitis, but sterility is uncommon.

Pancreatitis is an uncommon complication and may manifest in the absence of parotitis. Hyperglycemia is temporary and reversible. Infection with the mumps virus has been suggested to be related to type 1 diabetes mellitus; however, studies have not been conclusive thus far.

Mumps-related deafness is one of the major causes of acquired sensorineural deafness in children. This complication is estimated to occur in 1 in 20,000 patients with mumps.

Prognosis

The prognosis is good.

Education

Children who are infected with mumps should not attend school or daycare centers until 9 days after the onset of parotitis.

When attempting to control outbreaks, schools should exclude susceptible students from attending affected schools. The susceptible students may return to school after immunization. Students who are exempt from mumps vaccination for medical, religious, or other reasons should avoid affected schools for at least 26 days after the onset of parotitis in the last person who was infected.

Measles (Rubeola)

Background

Measles, also known as rubeola, is an acute, infectious, highly contagious disease that frequently occurs in children. In the United States, the incidence of measles has dramatically decreased as a result of the measles vaccine; however, it remains a significant problem in developing countries.

Pathophysiology

The measles virus is a paramyxovirus belonging to the Morbillivirus genus. The paramyxovirus can survive for as long as 2 hours in the air and on surfaces. Measles is spread by direct contact via droplets from respiratory tract secretions in patients who are infected. It is considered one of the most communicable infectious diseases.

The initial site of infection is the respiratory tract epithelium. Multiplication of the measles virus in the respiratory tract epithelium and regional lymph nodes is followed by a primary viremia, with spread to the reticuloendothelial system. A secondary viremia occurs upon breakdown and necrosis of the reticuloendothelial cells, and the virus infects the leukocytes. During the secondary viremia, infection may spread to the thymus, spleen, lymph nodes, liver, skin, and lungs.

Frequency

In the United States, measles generally occurs in late winter and spring. Prior to the use of the measles vaccine in 1963, approximately 500,000 cases and 500 deaths were reported each year. Epidemic cycles occurred every 2-3 years. Greater than 50% of the population had measles by age 6 years, and greater than 90% were reported to have had it by age 15 years. After licensure of the vaccine in 1963, the number of reported cases of measles dropped by more than 98%, and the 2- to 3-year epidemic cycles no longer prevailed.

From 1989-1991, the incidence of measles rose significantly, with approximately 55,000 cases reported in this 3-year period. The highest number of cases occurred in children younger than 5 years. These cases were prevalent in Hispanic and African American populations. This prevalence was determined to be a result of low vaccination rates among preschool-aged children in these groups. The incidence of measles decreased after this period, and since 1993, fewer than 500 cases have been observed in most years.

From 2001-2003, state and local health departments reported annual totals of confirmed measles cases as 116, 44, and 56, respectively, with a total of 216 cases. In 2002, a record low measles rate of 0.15 cases per million individuals was reported, representing a 59% decrease from the rate reported in 2000, which was the lowest previously noted.40

Persons who are at higher risk for measles are unvaccinated individuals in colleges and postsecondary institutions because of large concentrations of susceptible persons. Others who are at risk of exposure to measles are those who work in medical facilities, regardless of whether they are medical or nonmedical staff. Others at high-risk are those who have refused vaccination for personal or religious reasons. Individuals who are traveling outside the United States are also at increased risk of being exposed to measles.

In March 2004, the Iowa Department of Public Health informed the CDC that a 19-year-old student had flown from India to the United States during an infectious stage of measles. Because of a nonmedical exemption, the students at this Iowa college were not vaccinated and 6 of them were infected with measles during a trip to India. The measles infection in these students while traveling abroad demonstrates how transmissible measles is in unvaccinated individuals.41

Since 1993, the largest outbreaks in the United States occurred in certain communities in Nevada, Utah, Missouri, and Illinois. These outbreaks occurred in groups of individuals who refused vaccination.

Since 1996, the largest outbreak to occur in the United States occurred between January 1 and July 31, 2008. During this period, 131 cases were reported to the CDC, compared with an average of 63 cases per year from 2000-2007. Of these cases of measles, 76% were in individuals younger than 20 years and 91% were in those who were not vaccinated or whose immune status was unknown. Additionally, 89% of these cases were brought in from or associated with importations of cases from other countries. Many of the imported cases were from Europe, where outbreaks were occurring at the time.42

Measles is often the first disease to occur in the United States when vaccination rates fall. Ongoing outbreaks appear to be occurring in Europe, where vaccination rates are lower than in the United States. The main countries involved are Austria, Italy, and Switzerland. In 2008, the United Kingdom reported endemic levels of measles cases due to a drop in vaccination levels.

Internationally, measles is endemic or epidemic in many parts of the world.

Mortality/morbidity

In the United States, the number of deaths caused by measles has been approximately 1-2 per 1000 cases. Young children and adults are at higher risk of death. Pneumonia accounts for approximately 60% of measles-related deaths. In children with measles, pneumonia-related deaths are most common, whereas in adults, encephalitis-related deaths are more common. Measles-related fatalities are increased in children with leukemia or HIV infection, who are immunocompromised.

Developing countries have higher rates of measles in children younger than 1 year. Malnourishment, particularly vitamin A deficiency, is a factor that influences the severity of measles. The mortality rate due to measles in populations with malnutrition can be as high as 25%.

Complications have occurred in as many as 30% of patients with measles. The complications are more severe in young children and adults. The most commonly reported complication from 1985-1992 was diarrhea, followed by otitis media and pneumonia.

In Africa, measles is the leading cause of blindness in children.

Race

No racial predilection is reported.

Sex

No sexual predilection is apparent.

Age

Prior to the routine administration of the measles vaccine, measles affected school-aged children. After that, other groups were affected, including preschool-aged children younger than 5 years and adults older than 20 years.

Clinical history

The incubation period for measles is the time from exposure to the prodrome. This period is approximately 10-14 days and is longer in adults than in children.

The prodrome phase lasts for several days and likely coincides with the secondary viremia phase. It is manifested by malaise, fever, anorexia, conjunctivitis, and respiratory symptoms. Toward the end of the prodrome and just prior to the appearance of the rash, Koplik spots are observed. The skin eruption of measles lasts approximately 5-6 days. The period of uncomplicated illness from the late prodrome to disappearance of skin lesions and fever lasts 7-10 days.

Physical findings

The fever in affected individuals can peak as high as 103-105°F. Patients also experience respiratory symptoms, such as cough and coryza (runny nose), which may resemble a severe upper respiratory tract infection.

Koplik spots are pathognomonic for measles. They are located on the buccal mucosa in the premolar and/or molar area. Occasionally, in severe cases of measles, several areas of the oral cavity may be affected by the enanthem. The intraoral lesions may persist for several days and begin to slough with the onset of the rash.

Koplik spots consist of bluish-gray specks against an erythematous background. They have been compared to grains of sand. As few as 1 spot and as many as 50 spots may occur. The lesions are plaquelike or nodular and oval or round. The measles rash often begins near the hairline and then involves the face and the neck; over the next few days, it progresses to the extremities and finally to the palms and the soles. The rash is erythematous and maculopapular and may become confluent as it progresses. It lasts approximately 5 days and resolves in the same order it appeared, from the face and the neck to the extremities.

Differentials

Koplik spots - Cheek chewing keratotic lesions

Large Fordyce granules

Workup

Laboratory studies

All specimens collected for viral culture in cases suggestive of measles should be sent to the nearest state public health laboratory or to the CDC. The measles virus can be isolated from blood, urine, or nasopharyngeal secretions. Clinical specimens and serologic specimens should be obtained at the same time and preferably within 7 days of the onset of the rash. The easiest method that aids in confirming the diagnosis is to test for immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody levels in a single specimen from an individual who is infected. A person who is infected or has received the vaccine initially has an IgM response followed by an immunoglobulin G (IgG) response. IgM antibodies are present for 1-2 months after exposure to the measles virus, and IgG antibodies are present for many years.

IgG tests (eg, enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay, hemagglutination inhibition, indirect fluorescent antibody tests) are conducted on 2 specimens. The first specimen is obtained during the acute phase (within 4 d of the start of the rash), and the second specimen is collected during the convalescent phase (2-4 wk later). Positive results show increased levels of IgG in the convalescent specimen.

Histologic findings

Oral and cutaneous lesions show necrosis of the superficial aspects of the epithelium with an inflammatory infiltrate that consists of neutrophils. Multinucleated giant cells, known as Warthin-Finkeldey cells, may be present in lymphoid tissue and lungs.

Medical care

No specific treatment is necessary for Koplik spots.

Patients should be referred to an appropriate physician for care. Supportive treatment is recommended. Appropriate antibiotic therapy is necessary for secondary bacterial infections.

The World Health Organization has recommended that vitamin A supplementation be provided for children with measles living in areas that have a documented vitamin A deficiency problem.

Intravenous and aerosol administration of ribavirin has been used to treat severe cases of measles in patients who are immunocompromised; however, the FDA has not approved this drug for the treatment of measles.

The measles vaccine currently used in the United States is a live-attenuated Enders-Edmonston strain (formerly called the Moraten strain). This vaccine is combined with the rubella and mumps vaccines and is administered as the MMR vaccine. Antibodies to measles virus develop in approximately 95% of children vaccinated at age 12 months and in 98% of children vaccinated at age 15 months. The vaccine induces long-term, if not lifelong, immunity to measles in 99% of individuals who receive 2 doses. Two doses of the measles vaccine in the form of MMR are recommended for all children. Individuals born before 1957 should be able to show documentation of immunity either via vaccination or via history of disease. In an individual who has been exposed to measles, administration of the live vaccine within 72 hours can provide long-term immunity.

Follow-up

Complications

No oral complications are reported from measles. Diarrhea, otitis media, and pneumonia are the more common complications encountered from measles infection.

One case of acute encephalitis occurs in every 1000-2000 cases of measles. Acute encephalitis begins 6 days after the onset of the rash; symptoms include high-grade fever, headache, stiff neck, convulsions, and coma. The fatality rate is approximately 15%.

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis is a previously unexplained CNS disease that occurs months to years after the initial measles infection. Progressive deterioration of intellect, convulsive seizures, motor abnormalities, and, eventually, death characterize subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

When measles infection occurs during pregnancy, the likelihood of early labor, spontaneous abortion, and low birth weight increases. Whether birth defects are caused by measles infection is questionable.

Prognosis

The prognosis is good in well-nourished children.

Rubella

Background

Rubella, also known as German measles, is an acute exanthematous viral infection that is similar in appearance to mild measles (rubeola) infections. It occurs in children and adults. The major potentially serious manifestations are observed in fetuses infected with rubella, resulting in various congenital defects.

Pathophysiology

The rubella virus is an RNA virus belonging to the Togavirus family and the Rubivirus genus. It is related to the group A arboviruses, specifically Eastern and Western encephalitis viruses. The rubella virus is unstable and is killed by lipid solvents, trypsin, formalin, ultraviolet light, and extremes in temperature and pH. The virus is spread via respiratory tract droplets from individuals who are infected. The virus replicates in the nasopharyngeal tissues and lymph nodes. A viremia results 5-7 days after initial exposure to other areas of the body. Patients are believed to be contagious when the rash is emerging. The virus may also be shed from the throat from 10 days before to 15 days after the onset of the rash. In congenital rubella infections, transplacental spread of virus occurs in the viremia stage. Infants with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) shed large amounts of rubella virus in their body secretions for many months.

Rubella is moderately contagious. It is most transmissible when the rash begins. Infants with CRS shed large amounts of the virus and can spread rubella to caregivers vulnerable to rubella infection.

Outbreaks continue to occur in populations that are susceptible to rubella infections, including those exposed to certain individuals who have religious or philosophic beliefs regarding personal exemption to vaccination. Other outbreaks have occurred in workplaces with employees who were born in countries outside of the United States that do not advocate routine immunizations, including Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Frequency

In the United States, the incidence of rubella infections is higher in late winter and spring.

Prior to the licensure of the rubella vaccine in 1969, the number of cases of rubella was high. The largest annual number was 57,686 cases in 1969. After 1969, the incidence of rubella dropped significantly. Fewer than 1000 cases per year were reported after 1983.

In 1988, the number of cases of rubella in the United States fell to an all time low of 223. However, in 1989, the number of cases nearly doubled from the previous year to 396. This was thought to have occurred with the rise in measles cases as a result of failure of timely vaccination of preschool children. After this resurgence, the number of cases of rubella fell steadily.

The demographics of rubella cases in the United States changed in the 1990s. It now occurs more frequently in foreign-born Hispanic adults who are unvaccinated or in those who have unknown vaccination status. Furthermore, rubella infection continues to occur in women of childbearing age who were born outside the United States.

Since 2001, the annual numbers of rubella cases in the United States have been the lowest in recorded history. Twenty-three cases were reported in 2001, 18 in 2002, 7 in 2003, and 9 in 2004. Approximately half of these cases occurred in persons born outside the United States, of whom most were born outside the Western Hemisphere.

Prior to the recommendations for the rubella vaccine, epidemics of rubella occurred every 6-9 years. The last major epidemic occurred in the United States in 1964-1965.

In 2005, the United States declared that it had eliminated endemic rubella transmission.43,44 However, future cases of rubella in the United States will likely be indicative of global occurrences of this disease. While rubella is endemic in many other parts of the world, the United States continues to maintain high vaccination rates in children, encourages vaccination in women of childbearing age (especially in those born outside the United States), and continues surveillance and response to future outbreaks of rubella.45

Internationally, rubella infections occur worldwide.

Mortality/morbidity

Complications of rubella infection occur more frequently in adults than in children.

Arthritis and/or arthralgias occur in as many as 70% of adult women who are infected with rubella. Joint involvement occurs at the same time as the rash and may last as long as 1 month.

Encephalitis is observed in 1 in 5000 cases and more often in adults than in children. Deaths rates related to encephalitis in the setting of rubella range from 0-50%.

Hemorrhagic complications occur in approximately 1 in 3000 cases and manifest more often in children than in adults. Thrombocytopenic purpura is common and likely due to low levels of platelets and vascular damage. GI and cerebral hemorrhage may also occur.

In 1964, 12.5 million cases of rubella were reported, with 20,000 infants born with CRS. In early pregnancy, rubella infection can lead to serious complications, including fetal death, premature delivery, and congenital defects. Spontaneous abortions and stillbirths are common. As many as 85% of fetuses infected during the first trimester are affected. Complications are rare when rubella infection occurs after the 20th week of pregnancy.

All organ systems may be affected in CRS. Some investigators have reported developmental defects, including enamel hypoplasia and delayed eruption of deciduous teeth; however, other groups have debated the validity of such findings in CRS. Deafness is the most common manifestation and, occasionally, the only one of congenital rubella infection. Ocular defects, such as glaucoma, cataracts, and retinopathy, are possible sequelae. Cardiac defects, including patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, and coarctation of the aorta, may be observed. Neurologic manifestations, such as microcephaly and mental retardation, are other potential complications.

Race

No racial predilection is reported.

Sex

No sexual predilection is apparent.

Age

Rubella is considered a childhood disease; however, it can affect adolescents and adults.

Clinical history

The incubation period is approximately 12-23 days. A prodrome is observed more often in older children and adults than in others; it lasts 1-5 days. Symptoms include low-grade fever, swollen glands, malaise, and upper respiratory tract symptoms. The rash of rubella follows the prodrome and lasts approximately 3 days. Lymphadenopathy can be observed as long as 1 week before the onset of the rash and up to several weeks later.

Physical findings

Symptoms are often mild, and 30-50% of patients are asymptomatic or subclinical. The major manifestation of rubella is the presence of lymphadenopathy involving the postauricular, posterior cervical, and suboccipital lymph nodes. The rash of rubella begins on the face and progresses down the body. The rash consists of erythematous macules and, at times, small papules.

Intraorally, an enanthem consisting of petechial lesions, known as the Forchheimer sign, is observed in approximately 20% of patients. Clinically, these dark-red papules are observed on the soft palate. These lesions may arise at the onset of the rash. Palatal petechiae are also occasionally observed. The Forchheimer sign is not pathognomonic of rubella infection.

Other manifestations of rubella infection include conjunctivitis, orchitis, and arthritis.

Differentials

Forchheimer sign

Trauma

Chronic cough

Infectious mononucleosis

Thrombocytopenia

Trauma from fellatio

Hemophilia

Leukemic thrombocytopenia

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

Nonthrombocytopenic purpura

Calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal motility disorders, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia (CREST) syndrome

Workup

Laboratory studies

The rubella virus can be isolated from various secretions, including nasal, throat, blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens. The virus should be isolated in all cases suggestive of rubella or CRS. Serologic analysis is the most common means of confirming the diagnosis of rubella exposure.

Enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay is a readily available and easily performed test. It is used to detect IgM antibodies early in infection or IgG antibodies during the postinfection and/or vaccination period. Positive IgM test results for rubella imply recent postnatal infection or congenital infection. False-positive results for rubella IgM have been documented in patients with positive rheumatoid factor, parvovirus infections, and positive heterophile testing for infectious mononucleosis.

Histologic findings

No intraoral histologic findings are specific to rubella.

Medical care

Treatment for rubella is supportive care. Patients should be referred to an appropriate physician for care. Individuals with rubella infection should be isolated from places, such as school and work, for 7 days after the onset of the rash. No specific treatment is indicated for the oral manifestations of rubella.

The currently used rubella vaccine is a live- attenuated virus. The rubella vaccine can be administered as a single agent or in combination with the measles and mumps vaccines as the MMR vaccine. Of individuals who are vaccinated, 90% or more are protected against clinical rubella for at least 15 years. A single dose of the vaccine likely provides long-term immunity. Immunizing postpubertal males and females is recommended. The goal of rubella vaccination is to prevent CRS.

Prognosis

The prognosis is good in postnatal rubella.

The prognosis is guarded in CRS, depending on the severity of the manifestations.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét